Veneers

- François Langin

- Sep 27, 2017

- 4 min read

Updated: Dec 3, 2017

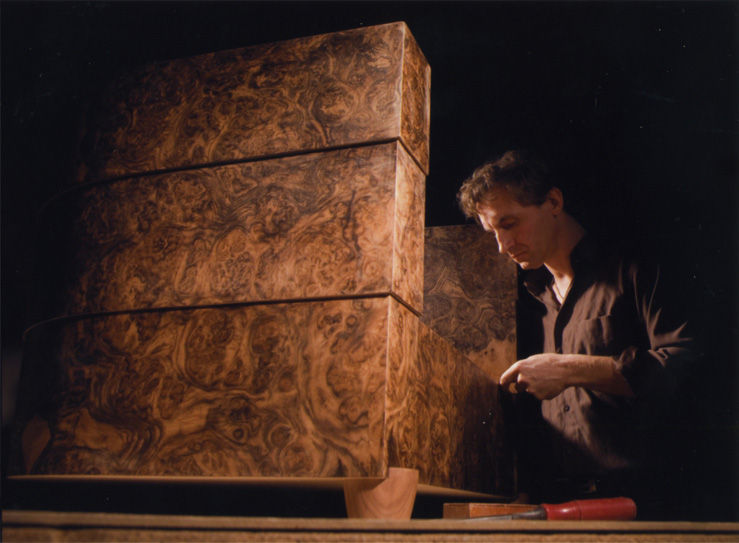

Craftsmanship focuses on grain and color of wood

Craftsman François Langin lifts a stack of rosewood veneer to his nose and breathes in the aroma.

"Ah," he says. "It's like perfume." His attraction to woods developed as a young boy when he spent days watching his elders in their woodworking shop in Annecy, France.

"When you work intimately with nature, it impacts you at the soul level," he says. "It's more than just a visual effect; it's emo-tional."

Today, Langin's specialty is blending veneers with solid woods - a result of his own evolution as a woodworker. Using exotics such as Makore, Narra, Bubinga, Imbuya, Avenge, Zebrawood, Aniegre and Macassar Ebony offer "unique aesthetics that you can't get with solid wood," says Langin, 42. Each type of veneer preseas distinct colors and grain, from tight, striated patterns to hose resembling animal stripes to others with the free-flowing organic shapes similar to granite's.

The process of working with veneer is to "unfold and reveal," he says.

Because such patterns can differ from tree to tree within a species, he often selects one tree to complete his project. The tree is cut into veneer, which unfolds in book-matched pattern for the look of continuous grain that flows throughout a room. These materials are showcased in kitchens, theater rooms and entertainment centers throughout Orange County.

"Working with veneers requires ongoing consumer education," he says. For many veneer has had the reputation of cheap craftsmanship. Yet, the J. Paul Getty Museum contains beautiful historical pieces constructed from veneers. Master furniture makers such as Andre-Charles Boulle, whose work is synonymous with the practice of veneering furniture, created exquisite designs with interesting color compositions and inlaid marquetry.

Langin laughs as he explains how a client grasped a better understanding of veneers after Langin explained how the entertainment center would look like the dashboard of a Rolls-Royce.

When Langin arrived in Orange County in the early 1990s, woodwork finishes tended toward whitewashed oak. But as design continued to evolve, clients found an appreciation for his early work with maple. Its closed grain and light color worked well with Mediterranean-style homes. As the requests for his built-in cabinetry designs increased, he moved from creating individual furniture pieces to large-scale room projects.

He finds inspiration for his designs in nature, the material itself. But most important, he tries to capture his clients' visions. As an artist, he thinks three-dimensionally, sketching his designs on paper in his Santa Ana studio workshop before creating a computerized drawing. A veneer is then chosen for the color and texture that will best enhance the design.

To those who voice environmental concerns, he explains that slicing rare woods into 1-millimeter layers means more of the wood's attractive surfaces can be used and appreciated, he says. "What a shame it would be to use the wood in a solid piece; you would lose all the patterns on the inside."

Langin says he uses only veneers regulated by the Forestry Stewardship Council and calculates precisely for the amount needed to eliminate waste.

"I have great reverence for the materials, which in some cases took 200 years to grow. It's my responsibility to make something beautiful with them."

Working with veneer is highly specialized, requiring more than $150,000 worth of equipment, which is why other woodworking shops call upon him.

First, each piece of veneer is cut to the proper width using a large guillotine. Cuts must be precise to get the continuous grain appearance in the finished product. Pieces of veneer are then stitched together with a fine thread. Stitching stays in place but is only visible on the reverse side.

Veneer must then adhere to a substrate before it can be shaped to fit into the design of the cabinet. Glue is applied to a substrate before the veneer is placed on top. These layers are then hand-fed into heated pressing equipment that applies 80 tons of pressure to as-sure the veneer adheres tight.

Next, the veneer is wrapped on the solid forms of the design to achieve the continuous pattern. "This is where the true artistry takes place," he says.

Once assembled, each piece of cabinetry receives a sealer, which adheres to the wood. Up to 10 layers of lacquer are applied for depth and protection. These light finishes - the compounds are Langin's trade secret - are meant to enhance the natural beauty of the wood, he says.

The result is a durable finish that feels like silk. Veneer finishes require dusting with a damp cloth and wiping dry to maintain.

Like haute couture in fashion, many of Langin's designs are exclusive to wealthy customers, including business moguls and Hollywood celebrities. However, there is a scope of his work that is more accessible. Prices for his kitchen cabinets and entertainment centers are comparable to those offered at high-end custom-design firms, he says. As a finishing touch, Langin practices the centuries-old tradition of signing his name where it can't be seen, along with good wishes for love, gratitude, peace and understanding.

LANGIN'S TIPS

How to care for fine wood and veneers:

Protect wood from prolonged sun exposure, which can cause long-term damage.

Use a humidifier in the winter and an air conditioner in the summer to keep the relative humidity in the room at 25 percent to 35 percent.

Avoid placing hardwood furniture directly in front of radiators, heating vents or fireplaces.

Do not slide objects across wood.

Place coasters or felt pads under accessories to protect the finish.

Do not place hot or wet objects on wood furniture.

Avoid placing plastic or rubber materials such as lamp bases or place mats on your furniture, as certain plastics contain ingredients that may damage the finish.

Rotate accessories on your furniture periodically to avoid creating permanent marks.

Avoid wax polishes - they attract dirt.

Avoid silicone polishes - they will seep into even the deepest finishes and may be difficult to remove.

Know that different finishes require different approaches in maintenance and protection. Oils and waxes are dust magnets, and once applied, they make it more difficult to keep the furniture dust free. A good lacquer or varnish finish requires little more than wiping with a damp cloth, followed by a dry one.

Comentarios